The Revolt of 1857, also known as the Indian Rebellion of 1857, was a major uprising against the British East India Company, which acted as the governing authority in India on behalf of the British Crown. It began on 10 May 1857 in Meerut with a mutiny of Indian sepoys and quickly spread across northern and central India. The revolt marked a significant turning point in Indian history and laid the foundation for future struggles for independence.

Revolt of 1857 Background

- The Revolt of 1857 was rooted in centuries of political, economic, social, and cultural grievances against British policies.

- After the Battle of Plassey in 1757, the British gradually expanded their control over India, which led to growing resentment among rulers, peasants, traders, artisans, and soldiers.

- Recurrent famine, excessive taxation, interference in religious practices, and economic exploitation created widespread anger.

- Local uprisings, tribal movements, and peasant revolts were common in various regions even before 1857.

Causes of the Revolt

The revolt had multiple causes, including economic hardship, political discontent, and social unrest among Indians. British policies disrupted traditional systems, burdened peasants with taxes, and created resentment among rulers. Many Indians were unhappy with the annexation of princely states, loss of political power, and interference in religion and customs. Corruption in administration and unfair treatment of soldiers added to the growing anger.

The immediate spark came from the issue of greased cartridges in the new Enfield rifles, but the revolt was the result of decades of exploitation and widespread dissatisfaction across society.

Economic Causes

Economic exploitation under British rule caused widespread poverty, discontent, and instability, affecting peasants, artisans, and traditional elites alike.

- Drain of Wealth: Indian revenue was diverted to fund British administration and military campaigns abroad, draining the local economy.

- Land Revenue Policies: Excessive taxation through Permanent Settlement, Ryotwari, and Mahalwari systems led to land alienation and peasant misery.

- Destruction of Traditional Industries: Handicrafts and local industries were ruined by cheap British machine-made goods, leaving artisans jobless.

- Agricultural Exploitation: Forced cultivation of cash crops like indigo and opium caused famines, food shortages, and oppression of farmers.

- Loss of Aristocracy: Displaced zamindars and landlords lost economic and political power, leading to instability and resentment.

- Widespread Poverty and Famines: Traditional workers faced unemployment, heavy taxation caused financial distress, and frequent famines added to popular discontent.

Also Read: Advent of Europeans in India

Political Causes

The British political policies alienated Indian rulers, nobles, and traditional elites, disrupting the political and social fabric of India.

- Doctrine of Lapse: Introduced by Lord Dalhousie, this policy annexed princely states that had no natural heir, including Satara, Jhansi, and Nagpur, angering rulers and their subjects.

- Annexation of Awadh: Taken over in 1856 under the pretext of “misgovernance,” this decision deeply hurt the local population and sepoys, many of whom hailed from Awadh.

- Disrespect to Rulers: Indian kings and nobles were humiliated; for example, Bahadur Shah II was stripped of authority and his heirs were barred from Red Fort succession.

- Loss of Privileges: Zamindars, taluqdars, and princes lost estates and traditional rights, creating resentment among the elite.

- Exclusion from High Positions: Indians were denied key civil and military roles, frustrating the educated and ruling classes who felt marginalized.

- Erosion of Local Authority: Chieftains, tribal leaders, and local rulers were sidelined, weakening traditional governance and fueling unrest.

Administrative Causes

British administrative policies were rigid, centralized, and culturally insensitive, fueling dissatisfaction among Indians and sepoys alike.

- Centralized Control: Power was concentrated in British hands, reducing the influence of local rulers, chiefs, and tribal leaders, causing resentment.

- Exploitative Land Revenue Systems: Policies like Permanent Settlement, Ryotwari, and Mahalwari imposed heavy taxation on peasants, leading to economic distress.

- Cultural Insensitivity: Attempts to impose Western education, legal systems, and administrative norms were seen as disrespectful to Indian traditions.

- Military Discontent: Indian soldiers faced poor pay, limited promotion opportunities, and discriminatory treatment compared to British soldiers.

- Lack of Representation: Indians were excluded from decision-making positions in administration and the army, increasing feelings of marginalization.

Socio-Religious Causes

The British reforms and policies disrupted traditional Indian society, religion, and social hierarchy, creating resentment across communities.

- Racial Discrimination: The British maintained a sense of social superiority and treated Indians, including elites, with contempt.

- Religious Interference: Reforms such as the abolition of Sati and legalization of widow remarriage were viewed as intrusion into traditional practices.

- Missionary Activities: Aggressive promotion of Christianity created fear of forced conversions among Hindus and Muslims.

- Alien Rule: The British remained socially aloof and never integrated with Indian society, increasing feelings of resentment.

- Loss of Religious and Social Prestige: Pandits, Maulvis, and other religious leaders lost their traditional influence under colonial policies.

- Disruption of Social Order: Reforms like land revenue policies and annexation of states weakened traditional hierarchies and destabilized society.

Influence of International Events

- British Weakness Perceived: The First Afghan War, Punjab Wars, and Crimean War strained British resources and created a perception of vulnerability.

- Psychological Impact: Indians believed that the British could be defeated, inspiring rebellion across regions.

Dissatisfaction Among Sepoys

- Religious and Caste Restrictions: Sepoys resented restrictions on wearing caste marks, proselytization by chaplains, and the requirement to cross seas, which violated caste rules.

- Unequal Treatment: Indian soldiers were paid less than British soldiers and denied foreign service allowances (Bhatta).

- Annexation of Awadh: The loss of their homeland increased resentment among sepoys.

- Military Grievances: Lack of promotion opportunities and perceived discrimination fueled anger against the Company.

Immediate Cause of Revolt of 1857

The immediate cause of the revolt was the issue of greased cartridges in the new Enfield rifles, which were rumored to be coated with cow and pig fat. This offended both Hindu and Muslim sepoys, as it violated their religious beliefs. Soldiers were required to bite these cartridges before loading the rifles, which increased their resentment. This incident acted as a catalyst, triggering the widespread mutiny that began in Meerut on 10 May 1857.

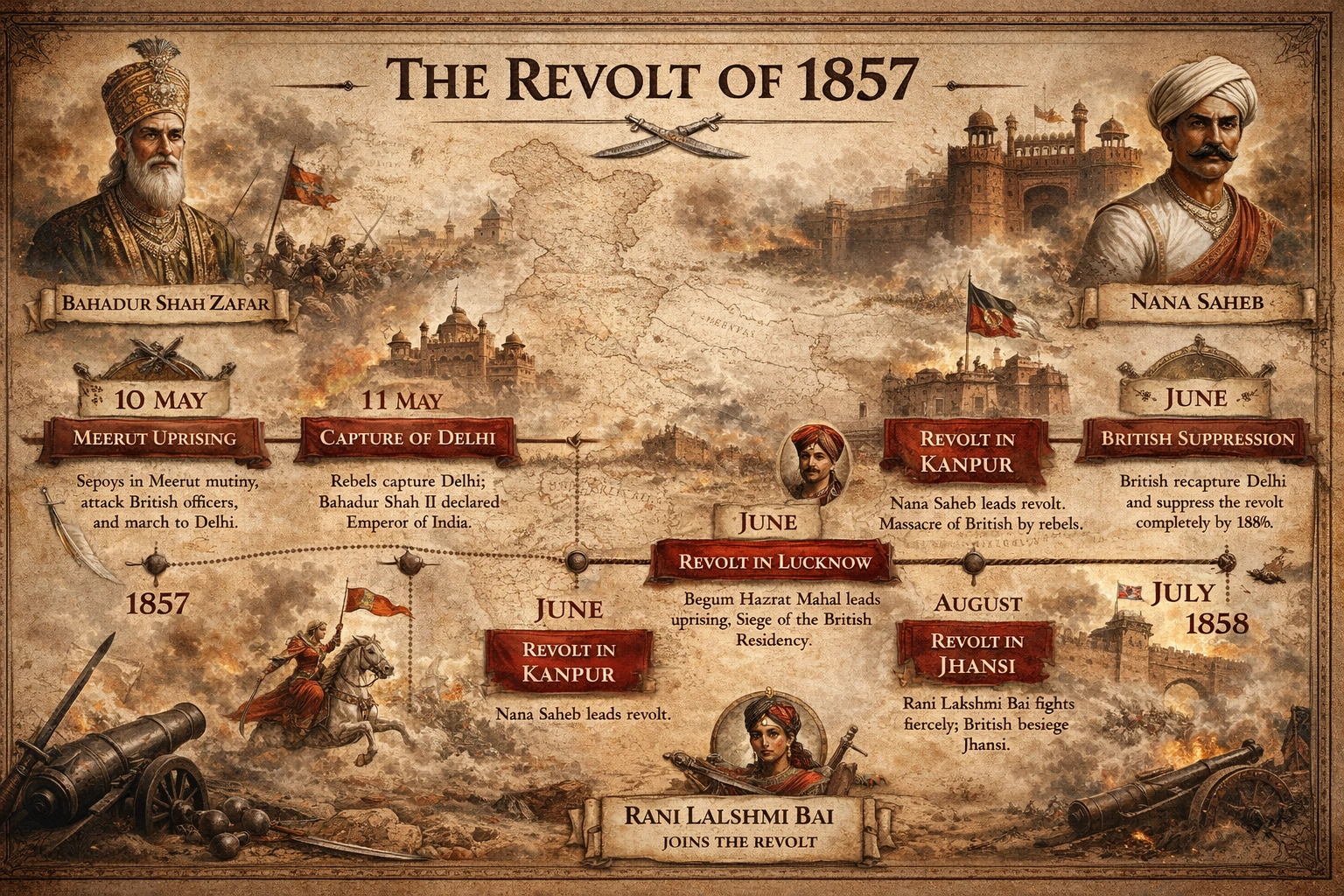

Revolt of 1857 Timeline

The Revolt of 1857 unfolded over more than a year, beginning with the mutiny at Meerut and spreading to large parts of northern and central India. Key battles, uprisings, and leadership actions marked the course of the rebellion. The timeline highlights the sequence of major events, locations, and leaders, helping us understand the flow of this historic uprising.

| Date | Event | Place | Key Leaders / Participants | Significance / Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 29 March 1857 | Mangal Pandey attacks British officers | Barrackpore (West Bengal) | Mangal Pandey | Early signs of sepoy unrest; Pandey was later executed |

| February 1857 | 19th Native Infantry mutinies | Berhampore | Indian sepoys | Unit dissolved; tension building among sepoys |

| 10 May 1857 | Mutiny of sepoys, outbreak of revolt | Meerut | Indian sepoys | Start of the Revolt; prisoners freed, officers killed |

| 11 May 1857 | Sepoys march to Delhi | Delhi | Sepoys, Bahadur Shah Zafar | Delhi becomes the center of the revolt; emperor recognized as symbolic leader |

| June 1857 | Revolt spreads to Kanpur | Kanpur | Nana Saheb, Tantia Tope | Kanpur uprising; British garrison besieged |

| June–July 1857 | Siege of Lucknow begins | Lucknow | Begum Hazrat Mahal | Awadh joins revolt; significant civilian participation |

| July 1857 | Capture of Jhansi by rebels | Jhansi | Rani Lakshmi Bai | Rani Lakshmi Bai emerges as key rebel leader |

| September 1857 | Delhi recaptured by British | Delhi | John Nicholson, British forces | Revolt’s epicenter falls; Bahadur Shah Zafar arrested |

| November 1857 | Retaking of Kanpur | Kanpur | British forces | Nana Saheb flees; British regain control |

| March 1858 | Recapture of Jhansi and Gwalior | Jhansi, Gwalior | British forces | Death of Rani Lakshmi Bai; Tantia Tope captured later |

| 1858 | Complete suppression of revolt | Northern & Central India | British forces | British regain control; Mughal empire formally ended |

| October 1858 | Proclamation of direct British rule | India | British Crown | End of East India Company rule; India under British Crown |

Centres of the Revolt of 1857

The Revolt of 1857 spread widely across northern and central India, covering areas from the neighbourhood of Patna in Bihar to the borders of Rajasthan. Several key cities and regions became major centres of rebellion, where sepoys, local rulers, and civilians actively resisted British authority. These centres witnessed fierce fighting, significant leadership, and local civilian participation.

Also Read: Decline of Mughal Empire in India

Lucknow

Lucknow, the capital of Awadh, became a significant centre of revolt after the British annexation of the region in 1856. Begum Hazrat Mahal, one of the ex-king’s widows, took charge of the uprising and organized both military and civilian resistance. She played a crucial role in leading the Awadh forces against the British, making Lucknow a symbol of organized leadership in the revolt.

Kanpur

Kanpur was another major centre, led by Nana Saheb, the adopted son of Peshwa Baji Rao II. He joined the revolt after the British denied him his pension, which created personal and political resentment. Though initially successful in capturing the city, British reinforcements recaptured Kanpur, and the revolt was suppressed brutally. Nana Saheb escaped, but his skilled commander Tantia Tope continued the struggle before eventually being defeated, captured, and executed.

Jhansi

The princely state of Jhansi was led by the twenty-two-year-old Rani Lakshmi Bai, who fought courageously when the British refused to recognize her adopted son’s claim to the throne. She organized the rebels and defended Jhansi against British attacks. After fierce battles, the British captured Jhansi, and Rani Lakshmi Bai escaped to continue her fight, ultimately dying in battle at Gwalior, symbolizing heroism and resistance.

Gwalior

After escaping Jhansi, Rani Lakshmi Bai joined Tantia Tope to march towards Gwalior, capturing the city temporarily. The rebels fought fiercely against British forces, with Rani Lakshmi Bai showing exceptional valor. However, Gwalior was later recaptured by the British, marking the final major defeat of these rebel leaders in central India.

Bihar

In Bihar, the revolt was led by Kunwar Singh, a royal from Jagdispur. Despite his advanced age of 80, he led his forces with determination against the British. His leadership inspired local zamindars and peasants to rise in rebellion, making Bihar a significant centre of resistance during the uprising.

Suppression of the Revolt

The Revolt of 1857 lasted for more than a year and was fully suppressed by mid-1858. On July 8, 1858, Lord Canning officially proclaimed peace, marking the end of the rebellion. The British used a combination of military superiority, reinforcements, and strategic suppression, punishing rebel leaders and civilians to reassert control over India.

Key Centres of Revolt and Their Leaders

| Place | Indian Leaders | British Officials who Suppressed the Revolt | Key Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Delhi | Bahadur Shah II | John Nicholson | Delhi was the symbolic center; Mughal emperor was captured and later exiled |

| Lucknow | Begum Hazrat Mahal | Henry Lawrence | Awadh revolt; significant civilian and military participation |

| Kanpur | Nana Saheb | Sir Colin Campbell | Initial success but recaptured; brutal suppression; Tantia Tope continued resistance |

| Jhansi & Gwalior | Rani Lakshmi Bai & Tantia Tope | General Hugh Rose | Fierce battles; heroic resistance; ultimate defeat and deaths |

| Bareilly | Khan Bahadur Khan | Sir Colin Campbell | North-western frontier uprising; harshly suppressed |

| Allahabad & Banaras | Maulvi Liyakat Ali | Colonel Oncell | Localized uprisings; limited but significant civilian participation |

| Bihar | Kunwar Singh | William Taylor | Inspired peasants and zamindars; rebel forces defeated after initial successes |

Leaders of the Revolt of 1857

The Revolt of 1857 saw brave leadership from both military commanders and civilian rulers who united against British rule. Leaders emerged across northern and central India, inspiring sepoys and civilians alike. Their courage, strategic actions, and sacrifices made them enduring symbols of resistance against colonial oppression.

| Leader | Region / State | Role & Contribution | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bahadur Shah II (Bahadur Shah Zafar) | Delhi | Last Mughal emperor; symbolic head of the revolt; sepoys recognized him as their emperor | Captured by British; exiled to Rangoon; Mughal dynasty ended |

| Nana Saheb | Kanpur (Awadh) | Led the Kanpur uprising; organized rebel forces; challenged British control | Fled after defeat; later life uncertain; became symbol of Kanpur resistance |

| Rani Lakshmi Bai | Jhansi (Bundelkhand) | Commanded Jhansi forces; fought bravely against British; allied with Tantia Tope | Killed in battle at Gwalior; became iconic figure of valor and resistance |

| Tantia Tope | Central India (Bundelkhand, Gwalior) | Rebel commander; assisted Nana Saheb and Rani Lakshmi Bai; led guerrilla campaigns | Captured and executed by British; remembered as skilled strategist |

| Begum Hazrat Mahal | Awadh (Lucknow) | Led the revolt in Lucknow after the British annexation of Awadh; organized civilian and military resistance | Defeated and exiled; symbol of women’s leadership in revolt |

| Kunwar Singh | Bihar (Jagdispur) | Led local zamindars and peasants in Bihar; fought British forces at age 80 | Died during the rebellion; inspired local peasant resistance |

| Azimullah Khan | Kanpur (Advisor to Nana Saheb) | Acted as political advisor and strategist for Nana Saheb; organized diplomacy and alliances | Played a key role in rebel coordination; part of Kanpur rebellion planning |

| Mangal Pandey | Barrackpore (Bengal) | Sepoy in the Bengal Army; attacked British officers in early 1857 | Executed; remembered as the spark of the rebellion |

| Maulvi Ahmadullah | Delhi & Surroundings | Religious leader; mobilized civilians and sepoys in northern India | Contributed to anti-British propaganda and local organization |

| Shah Mal | Meerut & Surroundings | Leader of local peasant uprisings; supported sepoy mutiny | Participated in early mutinies; represented civilian participation |

Reasons for Failure of the Revolt of 1857

The Revolt of 1857 failed because it lacked unity, coordination, and modern military strength, despite widespread participation. Regional leaders fought bravely, but differences in strategy, resources, and ideology prevented a sustained and organized resistance.

1. Limited Geographical Spread:

- The revolt was mainly confined to northern and central India; southern, western, and eastern regions were largely unaffected.

- Previous harsh suppression in these areas discouraged large-scale uprisings.

2. Lack of Unity Among Indians:

- Indian rulers, zamindars, and aristocrats often supported the British or remained neutral.

- Differences in interests among sepoys, peasants, and landlords hindered a common cause.

3. Poor Leadership and Coordination:

- Rebel leaders like Nana Saheb, Rani Lakshmi Bai, and Tantia Tope were brave but lacked centralized leadership.

- There was no unified strategy or central command to coordinate military actions across regions.

4. Inadequate Weapons and Military Training:

- Rebels mainly had swords, spears, and outdated firearms, while the British had modern rifles, artillery, and disciplined regiments.

- Lack of ammunition, training, and military discipline weakened rebel forces.

5. Absence of Modern Strategy:

- Rebels fought bravely but had no long-term political or administrative plan to govern liberated territories.

- British forces, using telegraphs and reinforcements, could outmaneuver and suppress the revolt efficiently.

6. Limited Participation of All Classes:

- Educated Indians and wealthy merchants often stayed loyal to the British, preferring stability over rebellion.

- Some peasants and zamindars withdrew after promises of land restoration or protection by the British.

7. Communal and Regional Differences:

Although Hindus and Muslims united in some regions, regional loyalties and personal interests often took precedence over national unity.

8. British Resources and Strategy:

- The British had superior weapons, reinforcements from other colonies, and effective communication via telegraph.

- They exploited caste, religion, and regional differences among Indians, following a ‘divide and rule’ approach.

Nature and Consequences of the Revolt

- The revolt was a combination of peasant uprising and military mutiny, reflecting widespread dissatisfaction with British policies.

- It forced the British to reform administration, army recruitment, and revenue policies to prevent future rebellions.

- The 1858 Royal Proclamation ended the East India Company’s rule and placed India directly under the British Crown.

- Though unsuccessful militarily, the revolt sowed the seeds of Indian nationalism and inspired later movements for independence.

Hindu-Muslim Unity During the Revolt

- The revolt witnessed cooperation between Hindus and Muslims at all levels, from leadership to common soldiers.

- Both communities recognized Bahadur Shah Zafar as emperor.

- Rebels respected religious sentiments, for example, imposing bans on cow slaughter where Hindus were present.

- Leaders like Nana Saheb and Rani Lakshmi Bai had Muslim and Afghan supporters, highlighting early Indian unity.

Results of the Revolt of 1857

The Revolt of 1857 was a turning point in Indian history, marking the end of the East India Company’s rule and bringing India directly under the British Crown. Though the rebellion was suppressed, it led to major political, administrative, and military changes that reshaped colonial governance in India.

1. End of Company Rule

The uprising marked the end of the East India Company’s dominion over India, which had lasted for nearly a century. The Company lost its administrative, military, and revenue powers, which were transferred to the British Crown, making India a formal colony of Britain.

2. Direct Rule of the British Crown

After the revolt, India came under direct rule of the British Crown. Lord Canning announced this at a Durbar in Allahabad on 1 November 1858 through a proclamation issued in the name of Queen Victoria. The administration was now handled by the India Office in London, representing the British Parliament, ensuring tighter control over Indian governance.

3. Religious Tolerance

The British promised respect for Indian religious and cultural practices to avoid future rebellions. They pledged non-interference in social and religious customs, addressing fears that had contributed to the revolt. Policies emphasized safeguarding traditions to maintain loyalty among Indian rulers and common people.

4. Administrative Changes

Significant changes were made in administration to stabilize colonial rule:

- The office of Governor-General was replaced by the Viceroy, who now acted as the direct representative of the British Crown.

- The rights of Indian rulers were formally recognized.

- The Doctrine of Lapse, which had allowed the annexation of states without heirs, was abolished.

- Indian rulers were allowed to adopt sons as legal heirs, restoring dynastic rights and political legitimacy.

5. Military Reorganization

The revolt exposed weaknesses in the Indian army, prompting major reforms:

- The ratio of British officers to Indian soldiers was increased to ensure tighter control.

- Armouries and key military resources remained firmly under British hands.

- The dominance of the Bengal Army was reduced, and recruitment was diversified across regions and communities to prevent future mutinies.

6. Political and Long-term Impact

- India was now governed directly by the British Crown, ending semi-autonomous company rule.

- The revolt influenced British policies, emphasizing loyalty, divide-and-rule strategies, and cautious reforms.

- Though the rebellion failed militarily, it sowed the seeds of Indian nationalism and highlighted the potential of united resistance across social and religious groups.

Revolt of 1857 UPSC PYQs

Question 1: The Revolt of 1857 was the culmination of the recurrent big and small local rebellions that had occurred in the preceding hundred years of British rule. (UPSC Mains 2019)

Question 2: Explain how the Uprising of 1857 constitutes an important watershed in the evolution of British policies towards colonial India. (UPSC Mains 2016)